MacOS 10.9.3 will sync contacts over USB and Wi-Fi again

▼ In order to sync an iPhone running iOS 7 with your Mac you need to run iTunes 11.1. The combination of MacOS 10.9, iTunes 11.1 and iOS 7 will no longer sync calendars and contacts between a Mac and an iOS device directly over USB or Wi-Fi: the only way to do this is using iCloud or other CalDAV and CardDAV servers.

For contacts that didn't bother me too much, although it's still enormously annoying that Apple takes away useful features like this whenever they feel like it. With no advance warning either. But for contacts, this created a problem for me. It's probably a bit irrational, but I really don't want to give my contact list to Apple/iCloud. (And certainly not Whatsapp/Facebook, which leaves Whatsapp only barely usable because you then only see phone numbers.)

Like I said, it's probably somewhat irrational, because my contact info is in other people's contact lists, so Apple, Facebook, the NSA and everyone else already has all this info anyway. However, the trouble with contacts is that unlike calendars, you really need to sync all of them entirely to be useful.

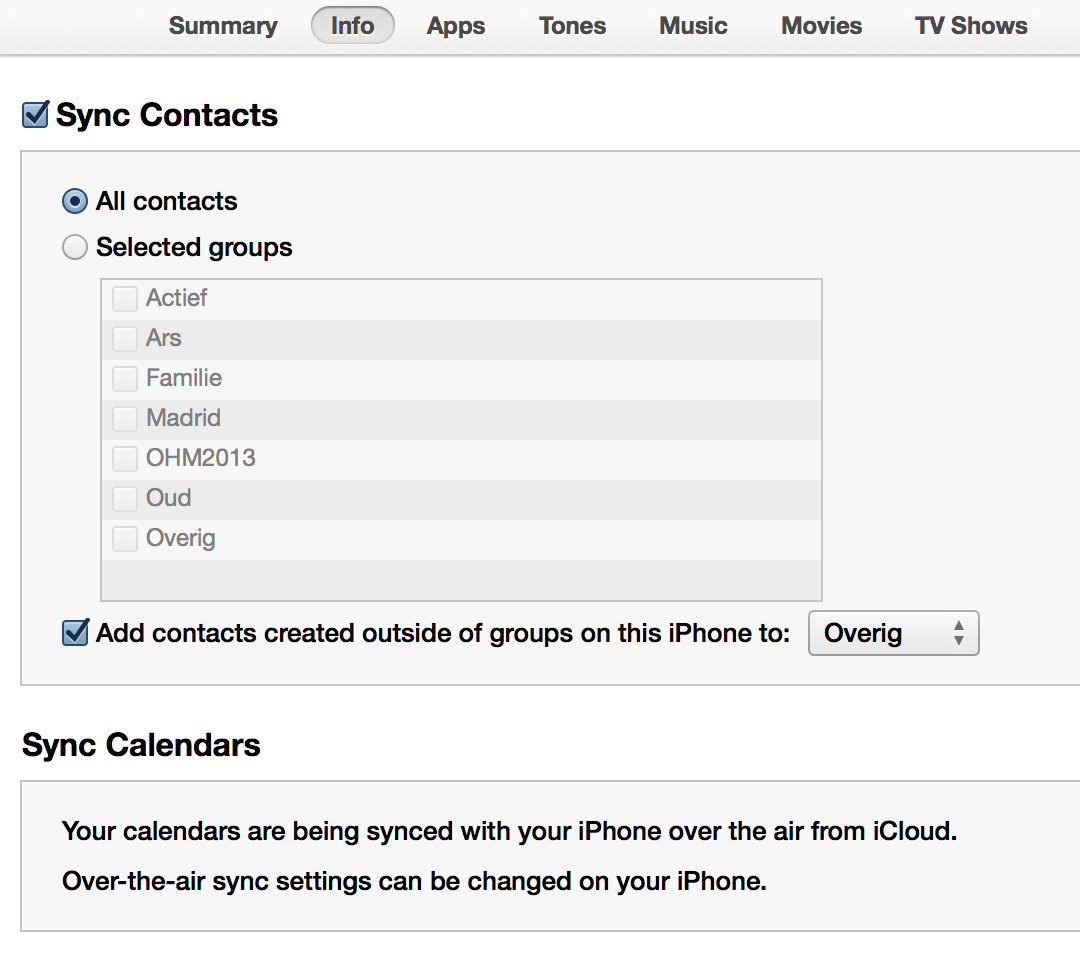

In any event, the good news is that as of MacOS 10.9.3 and iTunes 11.2, it's again possible to sync contacts using the USB cable or over Wi-Fi:

Unfortunately, syncing contacts with iPods remains missing in action, and syncing calendars also wasn't brought back.

There are also some interesting changes to podcasting in iTunes 11.2, which finally fixes the long-standing bug where manually downloaded podcasts wouldn't be deleted automatically after they had been played. And the Podcasts application on the iPhone now gains Siri integration in version 2.1, and also lists more episodes per screen and improves support for shownotes (tap on the album art during playback).

Permalink - posted 2014-05-20